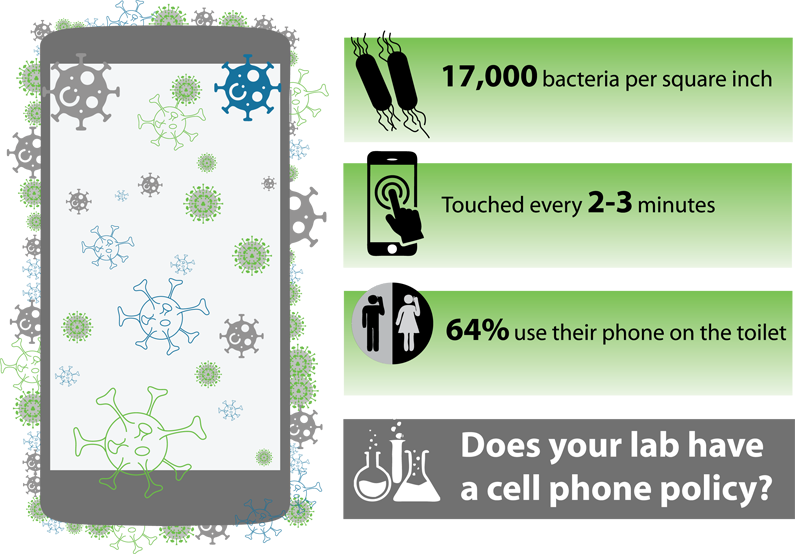

On average, Americans check their phones within 10 minutes of waking up, and continue checking them about 344 times per day, or once every 2.8 minutes during waking hours. That means most of us touch our cell phones more than any other object in our lives.

All that contact means our constant digital companions are also the dirtiest. The average cell phone has 17,000 bacteria per square inch — many times more than the average toilet handle. But since 64% of us also admit to using our cell phone on the toilet, that shouldn’t be too surprising.

Using mobile devices in the lab presents an obvious risk of cross-contamination. Harmful substances and microbes in the lab can hitch a ride home on a cell phone, and substances brought into the lab on cell phones can contaminate research. Opponents also point out that mobile devices can be a distraction, a potential ignition source and an information security risk. Nevertheless, a 2017 review of 245 laboratory workers worldwide showed 60% use their phones in the laboratory, and 92% had witnessed phone usage by others in the lab.

Despite the risks, asking people to part with their cell phones — even temporarily — can meet with stiff resistance. “We’ve already had someone complain to Human Resources, so this could quickly become a mess,” said one environmental health and safety supervisor, surprised at how quickly the discussion escalated when she brought up cell phone policies at a lab staff meeting.

Cell Phone Policies: What Are Other Organizations Doing?

Many academic institutions, such as Boston University, base their policy on guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), which takes an unambiguous stance against phones in labs: “The use of personal electronic devices should not be allowed . . . any time chemicals, hazardous materials, or biohazardous materials are used in the laboratory.”

University of Birmingham (UK):: “Mobile devices may be prohibited or restricted in labs handling chemicals (which is likely to be all laboratories), and this should be assessed on a case by case basis.”

University of Connecticut: “No cell phones or other electronic devices may be used at any time in the laboratory.”

Rather than prohibiting cell phones, the Cornell University lab safety manual states: “All labs are strongly recommended to have a means of communication in the event of an emergency. This can include a phone or cell phone.” Cornell has also produced an informal safety video about safely using cell phones in labs.

Florida State University policy states: “EH&S discourages the use of cell phones and other electronic devices in the laboratory. Before using a cell phone, lab workers should remove PPE.”

Montana State University recommends “a self-enforced, common sense policy . . . We advise that personal devices only be used in the lab as needed for research-related communication.”

University of Nottingham (UK): “Personal mobile phones and music players must not be brought into or used in laboratory areas where . . . There is a high risk of them becoming contaminated with any of the hazardous substances being handled in the laboratory.” However, the policy also acknowledges that “there may be situations, such as lone working, where it is important to ensure the availability of a mobile phone as a control measure.”

Oklahoma State University: “No cell phone or ear phone usage in the active portion of the laboratories, or during experimental operations.”

University of Washington: “Cell phones and pagers are not allowed to be used while working in the undergraduate laboratories, to prevent any distractions from leading to mistakes or accidents.”

After copying the CLSI guidelines (above), the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee policy acknowledges: “Due to the integration of cellphones in to everyday life, this policy may be difficult to enforce at all times in the laboratory.”

A 2015 study found that some people are so attached to their phones that they actually experienced anxiety and decreased cognitive function when their phones were placed just a few feet out of arm’s reach.

Of course, there are real-world reasons why we feel compelled to keep our devices close. Cell phones can be expensive and may carry sensitive personal and financial information. Parents and caretakers who work in a lab want to be available for their family members. Mobile apps have become an everyday tool in some labs, and cell phones are the only means of emergency communication in others. (See box, “Emergency Communications.”)

For these and other reasons, an outright cell phone ban may be unrealistic for most labs. “Most institutions don’t prevent people from bringing the cell phone into the lab unless it’s a BSL-3 or BSL-4,” said Ian Olesen, who teaches biosafety for the Laboratory Safety Institute.

What most labs can do, Olesen said, is regulate the use of cell phones. For example, many labs have a policy prohibiting the manipulation of mobile devices with gloved hands or placing phones on any lab surface.

“I allow cell phones in lab except during quizzes and exams but we provide ordinary zip-lock sandwich bags to put the phones in so that they are protected and don’t carry contamination out of the lab. Sort of like gloves for the cell phones,” said Sandra Koster, a senior lecturer at the University of Wisconsin, on the DCHAS-L online discussion group.

Cell phones in labs can be a sticky subject, but ignoring the issue doesn’t make it go away, either. A well-communicated policy protects people, laboratory research, and cell phones.

Emergency Communications: Getting Through When Everything Goes Down

Unfortunately, no single communication technology is 100% Armageddon-proof. For every story of someone who was able to get through on a landline when cell service was out, there is another story when the opposite was true. Much depends on what kind of disaster it is and which infrastructures are damaged.

When it's time for budget talks, landlines are frequently on the cutting block because “everyone has a cell phone nowadays.” But before cutting the wire, consider the cons:

- Cell towers run on electricity, which means mobile phones may become useless in a major power outage. (This point is losing ground, however, as more cell towers are being built with backup generators.)

- Networks can become quickly overloaded when everyone is trying to call at the same time.

- Even in normal conditions, every wireless network has dead spots. (Can you hear me now?)

- Cell phone batteries run out, most in about a day.

- A cell phone may not be immediately reachable when needed. What if it was left in the car?

If you use a cell phone, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recommends texting rather than calling to avoid tying up voice networks, and because data-based services like texts and emails are less likely to experience network congestion.

Landlines may seem like the more stable option, but they are not guaranteed not to fail, either. Switching equipment and the telephone lines themselves may be damaged in a disaster. For this reason, most regulatory agencies don't indicate a preferred means of emergency communication. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) leaves it up to each employer to determine whether to use a landline, a cell phone, or even a manual pull box alarm (29 CFR 1910.165(b)(4)). However, although OSHA does not specify either landline or cell, the fire department or another local agency may have their own requirements.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) mandates that all hazardous waste generators (large or small) have “immediate access to an internal alarm or emergency communication device” (40 CFR 262.16(b)(8)(iv) and 262.254). When one inquirer asked specifically if a mobile phone counts as such an emergency communication device, the EPA responded in 2016: “Although cell phones are a useful means of communication, they should not be relied upon solely to satisfy this requirement.” Score another one for the trusty landline.

Depending on the situation, phones, two-way radios, satellite devices, or even an old-fashioned whistle could be useful in a disaster. More important than the specific technology is having a well-trained, knowledgeable staff that can quickly assess the situation and make intelligent judgment calls. To paraphrase Kenny Rogers:

You gotta know when to hold ‘em,

Know when to phone ‘em,

Know when to pull the alarm

Know when to run.

Emergency planning is one of the topics covered in all one-, two- and three-day courses from the Laboratory Safety Institute.