Last year, every academic lab fatality that happened in the world happened in China, prompting concerns over the state of lab safety in the People’s Republic. The Laboratory Safety Institute’s memorial wall, a webpage that tracks lab deaths worldwide, lists three deaths in China from chemical explosions and one from lab-acquired Monkey B virus.

A study published January in the Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries reports: “The past two decades have seen a rise in university laboratory accidents in China.” The seven study authors, from Canada, China, Korea, Taiwan and the U.S., found 102 lab-related injuries and 10 fatalities at Chinese labs between 2000 and 2018. The report also noted that some incidents are never made public, so the real numbers are likely higher.

What's more alarming than the uptick in lab fatalities is the lack of information published about them. For the incidents that are known, details are scarce. Official reports frequently omit essential information useful for preventing future accidents, such as the specific substances involved and what safety precautions were taken (or not taken).

This comes on the heels of wider concerns over transparency in China since the first case of COVID-19 was discovered in Wuhan in December 2019, but Chinese news media did not officially acknowledge the seriousness of transmissibility until January 20, 2020.

The Jiaotong University explosion in 2018 was the first university lab accident in China for which the results of an official investigation were reported on a government website. Significantly less information has been released regarding other lab fatalities.

Besides the dearth of information released publicly, some Chinese institutions do not even document accidents internally, reasoning that “many laboratory accidents have only minor impacts resulting in few injuries or losses,” say the study authors.

With a shortage of accident information to start with, it's not surprising that root cause analysis is seldom on the radar. Li Jian, general manager of Lanxum Safety Tech told Chemistry World in 2016: “In China, the focus is on preventing the same accident happening again by, for example, replacing a problematic piece equipment. In the West, more attention would be paid to identifying systemic safety failings.”

Yet, in its 20-year analysis of lab safety in China, the study published in January found that only 17% of accidents may have been related to equipment failure. It traced the majority of cases to improper or inadequate training, hazard analysis, or safety information.

“The problem is lab safety has never been prioritized,” Luo Min, a chemistry professor at Ningxia University told Chemistry World. “With surging research funding, many Chinese labs have installed more advanced and costly instruments than their counterparts in the West, but investment in safety training is far from adequate,” the article continued.

China's Safety Challenges

Lab safety in China is a complex and multi-faceted issue, but the study authors believe that improving accident reporting is the one single factor that stands to make the biggest difference.

“A database on university laboratory accidents is currently not available in China, and it is also rare worldwide, which create difficulties for root cause analysis and prevent learning from accidents among all university laboratories,” the report said.

China also has one of the highest student populations in the world, which could be one obvious factor affecting the number of lab incidents. The number of graduate students enrolled in science-related disciplines in China mushroomed from 90,000 in 2000 to about 5.3 million in 2019, and the number of labs grew along with them.

Jason Chruma, who was a professor and then assistant dean at Sichuan University in Chengdu from 2012 to 2020, told Nature that he sometimes saw crowding-related safety issues firsthand during his time there, such as students conducting chemical reactions in hallways because there weren’t enough fume hoods in busy labs.

Still, sheer population does not itself cause accidents. Experts point to deeper issues in safety culture and protocol.

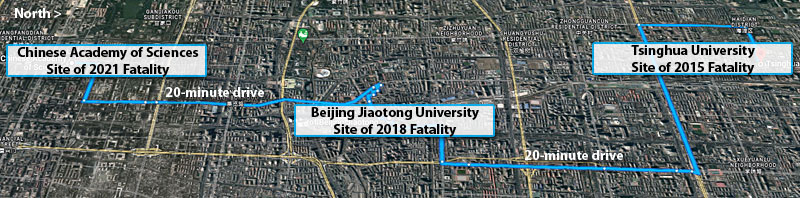

Although China’s Ministry of Education has repeatedly ordered extensive lab safety reforms, campaign-style calls for change typically ring hollow. The day before the incident at Tsinghua University that killed a postdoctoral researcher in 2015, the Ministry of Education urged universities and schools to carry out safety inspections. After the accident, they launched another nationwide lab safety examination.

Three years later, when another fatal lab accident killed three researchers at Jiaotong University, the Ministry of Education again ordered that “laboratory safety facilities and related guarantee systems should be overhauled to ensure that essential safety facilities and equipment function effectively and sufficient funds are invested in safety,” according to China Daily. Three years after that, an explosion at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing (only a 20-minute drive from Jiaotong) killed another graduate student.

“Compared with 20 years ago, lab safety in China has definitely made significant progress,” said Samuel Yu, director of the Health, Safety and Environment Office at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology in an article published January in Nature. He pointed to the addition of fume hoods and emergency showers, particularly at leading universities, as a hopeful sign.

Although there are problems that make lab safety in China a unique challenge, the same fundamental safety issues that exist in China exist everywhere. The Laboratory Safety Institute emphasizes that creating and nurturing a culture that encourages open reporting and sharing of accident information (as well as close calls and near-misses) is a crucial element in developing effective lab safety programs throughout the world. The Lab Safety Institute has been providing lab safety consulting and education worldwide for almost 45 years.